Tisha Tucker

Uniform Essay

by Tisha Tucker

I don’t recommend going to jail. It’s cold. It is scary. There is no privacy. There are angry people everywhere. It is oppressive. It’s aggressive. There are no answers to the questions you can’t ask. Any information you do manage to gather is incomplete, or conflicts with the information you squeezed out before it.

Worst of all – is the powerlessness and inexistence of choice.

You have no choice — in where to be — what to eat — when to wake — when to sleep. Your fate lies completely in the hands of those who don’t give a f*** about you. You are guilty until proven innocent, your only choices being 1) obey the rules or 2) resist the rules and be further confined, restricted, and punished and face potentially more jail time or solitary confinement.

On January 14, 2006, I was arrested for interference with a lawful occurrence and simple assault against a police officer. I was held for 17 hours at the Fulton County jail in Atlanta, Georgia until I was released on bail in the amount of $2400.

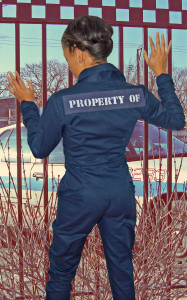

There are unique feelings with every stage of an arrest, from being handcuffed, to sitting in the back of the cop car, to sitting in the holding area. One of the most intense and scariest moments, however, was when I had to strip down completely naked (in front of an officer and other inmates) and surrender my personal clothes for a set of blue scrubs marked “Property of Fulton County”.

Jail uniforms were originally striped black and white. This style was mostly phased out in the early 20th century as they were seen as a symbol of shame, though jails in some Southern states still use them. Today, scrub style uniforms are most common. Some jails use a color system to easily categorize inmates. Orange scrubs mean an inmate is violent or unruly; blue means the inmate was accused of a misdemeanor or nonviolent felony and is low threat; quilted green smocks indicate the inmate is suicidal.

Outside the jail walls, the uniform is meant to be easily identifiable so that an inmate can be easily spotted and captured should they execute an escape.

Inside the jail walls it is meant to do the opposite. The uniform strips you of all personal identity and story and is a reminder that you are like everyone else there. Your person only matters if you somehow escape out. And then, you only matter until you’re thrown back in. Your story, your context, your spirit, means nothing. You wear orange, therefore you are dangerous. Period.

Though I knew that I was wrongfully arrested and felt angry about it, needling my arms into the sleeves of the shirt and stepping into the pants of the far too large blue jail scrubs felt like an admission of guilt. Immediately, I felt significantly more powerless than I had before, behind jail walls, in my own clothes. It felt permanent. I was suddenly the property of Fulton County.

Police officers are taught to control a situation, not to diffuse it. And though I can’t imagine the challenge of the crazy, sometimes life threatening, situations they have to face every day, how they personally exercise control and what they perceive as threatening are influenced by racism, as is the system that trains them.

Unlike an accident where intentional choices create unintentional consequences, the police officer knew the consequence of his choice when he arrested me and knows the far-reaching consequences of arrests, particularly for those who don’t have resources to hire legal assistance or who have prior offenses. These kinds of arrests cost taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars and jeopardize the futures of the thousands involved and are often the result of police officers abusing their power (while not following protocol) and of a justice system that legalizes discrimination against people of color. The impact of a conviction lasts a lifetime and often means “being relegated to a permanent second-class status in which a person is denied the right to vote, automatically excluded from juries, and subjected to legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to education, and public benefits.”

It’s no accident that while people of color make up about 30 percent of the United States’ population, we account for 60 percent of those imprisoned. There are more African Americans under correctional control today — in prison or jail, on probation or parole — than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began.

The last 30 years has seen massive incarceration of African Americans. The prison population grew by 700 percent from 1970 to 2005, however neither crime rates, nor population increase can explain the dramatic increase.

Michelle Alexander’s brilliant book The New Jim Crow offers an explanation:

Crime rates have fluctuated over the past few decades — and currently are at historical lows — but imprisonment rates have soared. Quintupled. And the vast majority of that increase is due to the War on Drugs, a war waged almost exclusively in poor communities of color, even though studies consistently show that people of all colors use and sell illegal drugs at remarkably similar rates. In fact, some studies indicate that white youth are significantly more likely to engage in illegal drug dealing than black youth.

Most people seem to imagine that the drug war — which has swept millions of poor people of color behind bars — has been aimed at rooting out drug kingpins or violent drug offenders. Nothing could be further from the truth. This war has been focused overwhelmingly on low-level drug offenses, like marijuana possession — the very crimes that happen with equal frequency in middle class white communities.

Some statistics:

- In 2005, 4 out 5 drug arrests were for possession and only 1 out of 5 were for sales.

- Most people in state prison for drug offenses have no history of violence or significant selling activity.

- Nearly 80 percent of the increase in drug arrests in the 1990s — the period of the most dramatic expansion of the drug war — was for marijuana possession, a drug less harmful than alcohol or tobacco.

- One in three black men can expect to go to prison in their lifetime.

- Blacks and Hispanics were approximately three times more likely to be searched during a traffic stop than white motorists.

- African Americans were twice as likely to be arrested and almost four times as likely to experience the use of force during encounters with the police.

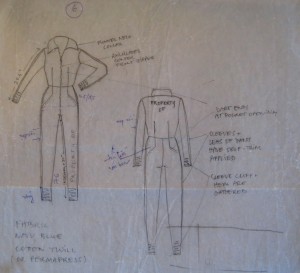

Though my participation in this project is based around my jail uniform and experience, everything about this beautiful project that a dear friend has created and that I chose to be a part of is opposite of that experience. I will be surrounded with love. I am safe. My measurements were carefully taken and this beautiful jumpsuit was created specifically for me, with my choices considered and respected. I chose what to share about my uniform story and how to share it. I chose to come to Chicago for the show. I chose what airline to fly. And as we share, and dance, and celebrate, and break bread, there are millions of people all over the world, in cold, scary, confined, powerless places that have been without choice for days, months, years, and decades.

On January 14, 2006, I did not make the choice to go to jail. If I had known that I was interacting with a police officer (he was not in uniform), there is no way I would have been arguing with him about whether or not a car would be towed.

I am in awe of the tens of thousands of civil rights leaders, protestors, freedom fighters, etc who so strongly believed in and fought for social justice that they made the choice to act in ways they knew would land them in jail. They chose justice despite the inevitability of jail, when the imprisonment experience back then was far more dangerous and unpredictable than it is today.

Most days I don’t think about freedom at all. I go on about my day, going to the job I choose, living in the apartment I love, eating whatever food I desire, talking to whomever I want to, anytime I desire. I can take walks whenever I want. Listen to whatever music I like. Stay up late. Wake up late. Take a trip to Peru. Celebrate holidays with family. Be angry and unreasonable without the consequence of more jail time or solitary confinement.

But when something reminds me of those 17 hours I didn’t have these simple freedoms, my heart is heavy for those without it and humbled by those who sacrifice and risk their lives for it.

We still have a long way to go.

Bio Tisha Tucker was born in Austin, Texas, raised in Los Angeles, California and has happily settled into Brooklyn, New York. She holds a Masters in Public Health from Emory University and works for a public health consulting firm. She loves old people and old things. She loves to dance, roam, and wander the city looking for new discoveries.