Mode of Production: Reclaiming the Revolutionary Potential of the Uniform

Mode of Production: Reclaiming the Revolutionary Potential of the Uniform

By Annemarie Strassel, PhD

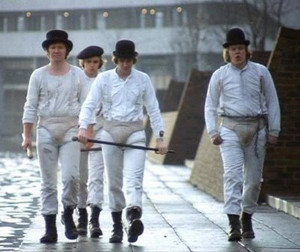

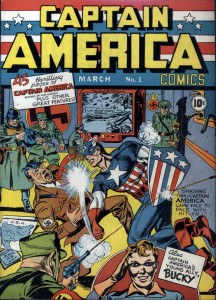

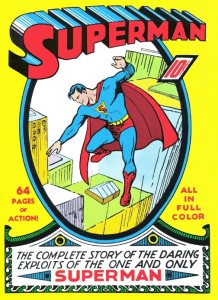

In the past, the future was imagined as a world in uniform. The pages of comic books and the world of sci-fi have long been littered with sleek unitards and metallic jumpsuits. Sometimes boxy, sometimes skintight, the unisex bodysuit once established itself as the seemingly inevitable uniform of the future. Consider the crew aboard Starship Enterprise. Captain America. The villains of A Clockwork Orange. Even the Little Prince. The fashion of the future, these visions portend, will be summed up in a single garment, worn daily and universally to equip bodies for radically new ways of moving and being.

In its brightest moments, the uniform signaled the triumph of reason over fashion in a world where functionality and unfettered movement trump vanity or other base human desires. In more dystopic visions of the future like THX-1138 or Fahrenheit 451, bodysuit uniforms symbolize the darker side of modernity’s demand for technical rationality, where free will and individuality are subjugated to the broader determination of the fascist state.

The future, otherwise known as the present, has turned out quite different. Today, style is more fragmented than ever. While runways and top fashion designers compete to define the season’s latest trends, the streets teem with a dizzying kaleidoscope of styles that live contemporaneously. Fast fashion retail giants like H&M pump out 24 separate clothing seasons a year. In the Cold War of fashion, the communists lost.

There was a time, however, when the bodysuit uniform possessed revolutionary potential that seemed to be the inexorable conclusion of modernity. It would capture the imagination of the European and American avant-garde between two world wars, and persist from this time forward in the visual iconography and temporal disjuncture of science fiction—a world of imaginary futures and fantasies of the present.

The aesthetics of uniformity sprang from experimentation in dress by artists and designers, who were radicalized by the socialist and communist revolutions that erupted in the 1910s. By the time of the Great Depression, the aesthetic evolved, as the Popular Front brought the United States to the brink of revolution and leftists worldwide banded together to combat the rise of fascism. Waves of organizing among workers in garment and automotive factories formed the backbone of a new powerful union movement. Economic exigency led millions of women to enter the workforce for the first time. As the world of industrial manufacture became the engine of social change, the radical wing of the avant-garde and leftists working in creative industries worldwide found inspiration in the world of mass production, making art that fueled broader social movements. In this moment, early futuristic visions of dress emerged in many forms akin to the factory jumpsuit, which functioned as a great equalizer and a tool for outfitting workers—literally and theoretically—for wage labor.

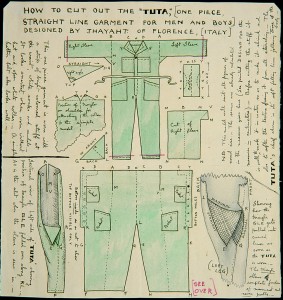

In 1919, Florentine designer Ernesto Michahelles designed the first jumpsuit, which he dubbed the TuTa. Its construction was strategically simple. Shaped like a T, the TuTa was cut from one piece of cotton and constructed with one straight cut, several seams, seven buttons and a belt. Michahelles renamed himself THAYAHT, a bifrontal palindrome, in keeping with the symmetry of his design.

Set against men’s suits of the day, with their tight collars, superfluous ties and made-to-measure construction, Thayaht’s TuTa insisted on absolute functionality. Made of cheap, sturdy material and easily reproducible, the TuTa was imbued with democratic potential. Thayaht even published the pattern in an Italian newspaper La Nazione to make it accessible to the greater public. He also created a similar variant for women. By fusing functionality with formal innovation and rejecting the autonomous status of art (that is, “art for art’s sake”), Thayaht’s creation was fundamentally anti-bourgeois. He was part of a broader movement of Italian futurists, experimenting with clothing that prepared the modern individual for what Umberto Boccioni described as the “vertiginous movement of human life.” Ever modest, Thayaht described his garment as “the most innovative, futuristic garment ever produced in the history of Italian fashion.”

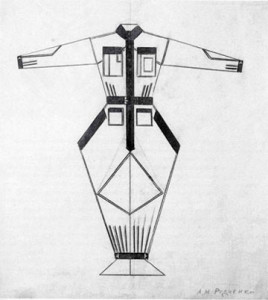

The wedding of art with objects of everyday use became a signature of the radical wing of the modernist avant-garde. Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, Productivists like Varvara Stepanova, her husband Alexander Rodchenko, and Luibov Popova designed jumpsuits for work and play to clothe threadbare shoeless peasants who found sustenance in state factories.

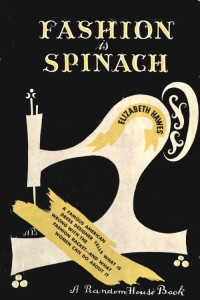

In the United States, Elizabeth Hawes, one of the first big names in American fashion, designed one-piece coveralls the same year she published Fashion Is Spinach (1938), a best-selling book that lampooned the fashion industry. In it, she lays bare the elitism of Parisian custom couture and the hollow democratic rhetoric of American manufacturers, who produced cheap, ill-fitting clothes en masse. She dreamed of designing “Fords” of fashion that cost $3.75 rather than $375, the price of custom dresses from her 5th Avenue boutique, without sacrificing quality, fit and beauty. 1940, Hawes left her design business to fight the war against fascism, organizing women workers in aeronautical factories with the UAW during World War II. Designing ensembles for the Red Cross, Hawes was among an emerging generation of designers who experimented in uniform design to clothe millions of women doing wartime work. Her contemporaries Bonnie Cashin and Vera Maxwell crafted snappy jumpsuits and wartime apparel that have become immortalized in the iconography of Rosie the Riveter.

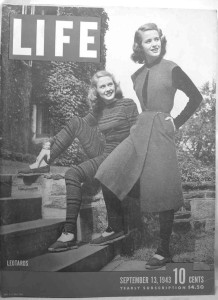

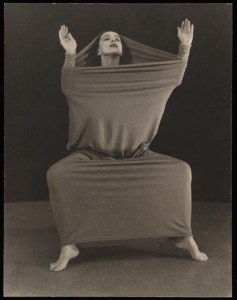

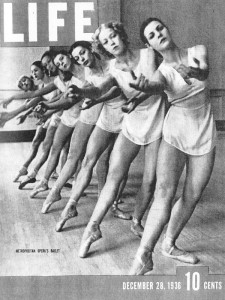

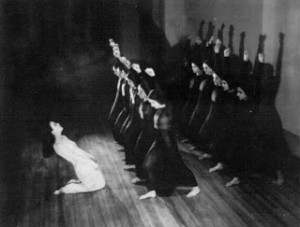

Advances in textile technology and improvements in knitting machines gave rise to nylon fabrics with newfound stretch and coverage, which in turn led to the seamless, one-piece unitard that has come to define dancewear of the modern era. Abandoning Grecian tunics in favor of spare silhouettes, Martha Graham transformed the sartorial vocabulary of modern dance to embrace futurism in dress rather than historical referents. Paring dress down to its simplest form, Martha Graham staged Lamentation in 1930, shrouded head-to-toe in one seamless, elastic monochrome tube to explore the dialectics of constraint and liberation using the tension between body and dress. Her contemporary George Balanchine in 1934 was the first to dress ballet dancers in uniform rehearsal practice clothes for public performance. Eschewing color in simple palettes of white and black, he achieved a minimalism on stage that embraced a look of near nudity. Freed from the weight of cotton and wool, from the stuffy confines of corsetry and tutus, ballet choreography became more athletic and driven by the modernist aesthetic of formal unity. Dressing men and women identically deemphasized gender and exalted form over narrative, creating onstage a visual coherence that has become the hallmark of avant-garde choreography. For Graham, this visual unity imbued her work with allusions to socialism and allegories of mass movement. Beyond the stage, one-piece head-to-toe “leotards” achieved popularity in the streets, gracing the cover of Life Magazine in 1944 as the essential component of the college wardrobe. In 1950, Vogue’s retrospective on fashion for the first half of the century hailed leotards as the garment that best captured the spirit of the 1940s.

In 1938, the year that Time named Hitler “Man of the Year,” the first issue of Superman made its debut, announcing the arrival of a new golden era of comic book superheroes. Between 1939 and 1941, DC and sister company All-American Publications, along with Marvel’s predecessor Timely Comics, introduced such popular superheroes as Batman and Robin, Wonder Woman, The Flash, Green Lantern, Aquaman, and Captain America. Superheroes brought with them ideals of American utopianism made manifest in the costuming and avenging exploits of the comic heroes as they hurled bowling balls and other objects at the heads of the Axis dictators. Clark Kent’s transformation to Superman made literal the transformative power of transitioning from stuffy suit to sleek unitard. In his new skin, his personal uniform, Superman was poised for flight.

Thayaht abandoned industrial design in the 1930s to study science and astronomy. After World War II he established an independent station for recording space information with the hope of providing proof of UFOs. His bodysuit of the future followed a similar trajectory. The basic model was one worn by parachutists, skiers and aviators, hence the name “jumpsuit.” This outfit was worn for every momentous aeronautical feat, from on the first transatlantic flight to first launch into outer space. In the process, jumpsuits went from the factory floor to the moon, from communist insurgency to cosmonauts, becoming petrified in form and meaning among the characters aboard the Starship Enterprise.

Today, NASA has been defunded, and the space race has been replaced by decidedly smaller ambitions in the world of nanotechnology, microbiology and the ever-shrinking world of handheld computing devices. Capitalism has devoured Russia and China, and decades of Cold War propaganda have demonized the cultural signifiers of the communist state, including the aesthetics of uniformity. As the labor movement dwindles to a less than 10% of the American workforce, the factory jobs that once formed the foundation of the middle-class have been shipped overseas.

And yet our world is awakening to the realities of Bangladesh and the new corporate totalitarianism of Walmart. Both feed on poverty and impart to consumers a world of cheap goods whose imminent obsolescence is preordained. In its place, we long for something more sustainable. Already in the food movement this kind of conscious consumerism has taken hold, bringing with it a push for a more intimate connection to the supply chain, a return to craft, and a deeper appreciation for how food nourishes our bodies and sustains our communities. Now it seems is the time to rethink fast fashion as we have fast food. Now is the opportunity to reclaim the political potential of the uniform. This icon of modernity, standing at the crossroads of aesthetic innovation and social revolution, between the factory floor and pulp fiction, demonstrates how powerful dress can be as an agent and signifier of social change.

Cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation in Uniform

Captain America

A Clockwork Orange costumes

The Little Prince

Fahrenheit 451

Thayaht in the TuTa

Pattern for the TuTa by Thayaht

Thayaht suit for women

Varvara Stepanovas’s design for sports uniforms ca. 1920

Production clothing by Alexander Rodchenko ca. 1922

Elizabeth Hawes Fashion Is Spinach

Uniform design by Vera Maxwell ca. 1945 for the Sperry Gyroscope Factory Workers

“Leotard” fashions grace the cover of Life Magazine 1944. At this time, skintight knit leotards were worn as one piece unitards under wrapped dresses

Martha Graham performing Lamentation-1937

Balanchine and the aesthetics of uniformity in dance

Martha Graham Dance Company 1930 and the aesthetics of uniformity

Captain American fights Nazis cover March 19, 1941

Superman’s first appearance in 1938

Charles Lindbergh posing with the plane he used for his first non-stop solo transatlantic flight in May 1927

Flight suit worn by Amelia Earhart in the 1930s

Neil Armstrong pre-Gemini spacesuit