Jamie Hayes

Uniform Essay

by Jamie Hayes

During the fall of 2012 I worked as a designer for a fair trade artisan group in Southwest China. At the end of my two months there, I went to Ho Chi Minh City to have many of the items in this project produced. While most participants’ projects were planned well in advance of my trip, true to form, I waited until the last minute to design my own uniform. I’m glad that I did, as my time in China greatly influenced my thoughts on fashion, self-expression, uniformity, and individuality.

Only 10 years ago, Kunming, the town where I am based, was a dusty frontier town of one million people (small by Chinese standards). The roads were made of dirt and filled with bikes and donkey carts. Now it is a smoggy, bustling city of six million filled with late model luxury cars, skyscrapers, Starbucks, H&M, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Louis Vuitton.

The young professionals of Kunming are gleefully entering this world of fashion and consumerism. And they are doing it in their own way. A popular look for young women is electric blue suede stiletto booties trimmed with marabou dyed to match, paired with dresses embellished with sequins, rhinestones, studs, tassels—ornamentations of all sorts all at once—the more the better. Young men sport Justin Bieber-style haircuts, copious amounts of gel, and slim-cut shiny silver suit jackets over designer jeans and pointy-toed loafers.

In contrast the old people in the city and many country folk wear cotton Mao jackets and pants in grays and blues paired with hats: a newsboy or short-brimmed hat in the city; straw hats in the countryside. The cuts are loose and comfortable; the fabrics are worn from years of wash and wear. Women wear pops of color beneath—floral print shirts or vests. In the countryside, shocking pink is especially popular. This outfit works for all occasions: farming, market day, travel, construction work, dance.

As an American observing China and its burgeoning capitalism, I think a lot about consumerism and its supposed companion, individuality. To my mind, the trendy, fast fashions of young office workers seem no less a uniform than the Mao suits of the old folks—and much less elegant. And yet, observing my co-workers brings back memories of the glee of new purchases paid for with my first adult paychecks; the initial fun of playing the role of “grownup”; finding my own style; embellishing myself with makeup, wearing body-conscious clothing, sparkling and shining. I try to imagine those feelings not only on a personal level, but also on a societal level, since disposable income, conspicuous consumption, and a wealth of consumer choice is new to China, especially in far-flung Yunnan Province. I can feel the excitement of growth and change in the air—in fact I can see, taste, hear and smell it, too. The noise, dust and pollution from the construction of new malls, roads, and offices are everywhere.

Amidst this environment, I look for my uniform. With visions of Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love in my head, I decide that I must have a cheong sam made. My co-workers are excited and teach me about the history of the cheong sam, or rather, the qipao as it’s called in Mandarin. The dress originated in the Qing dynasty when the Manchu ruled over China and the now-dominant Han group. And yet, I’m told that the qipao is again in vogue with intellectual Han women as an expression of traditional Chinese culture. We plan to visit my coworkers’ favorite tailor, but never find the time because we work too much.

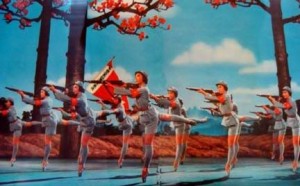

Instead I try to design myself something based on the Mao jackets that I love so much. I come across beautiful images from one of the model operas commissioned by Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, during the Cultural Revolution: The Red Detachment of Women. I watch the opera and do not understand the words, but am fascinated by the central role of women in this work and their athleticism, power, and militant beauty. But I do not find my uniform. Everything I draw feels contrived and vaguely Napoleonic.

I continue to research[1] and learn that, contrary to popular belief, even though most people wore Mao jackets during the Cultural Revolution, uniformity of dress was never a requirement of the Communist government. In fact, trousers and jackets were already the traditional garb for most women prior to 1949, except for a small minority of urban middle and upper class women who wore close-fitting silk qipao. However, in 1955, once the dust of the revolution settled and the economy became more stable, the issue of dress was addressed head-on by the government, who convened a forum on the subject with representatives from the worlds of art, music, writing and trade unions. The panel explored many of the same topics that I am exploring in this uniform project: the role of the worker, women’s roles/gender issues, class, hierarchy, individuality, economics of production, durability, ease of wear; and more broadly, the social meaning of dress.

I find the forum’s conversation fascinating. A man on the forum argues for the return of the formal qipao: “It makes women look gentle and graceful. Of course it is not very convenient for movement, but as long as you don’t run a race or do something like that, it is all right.” A female labor union leader counters: “It is too inconvenient. Besides I don’t agree that it is either graceful or beautiful. We don’t want uniformity. We want new styles, but they must be comfortable and becoming without getting in our way.” The President of the Arts Academy sums up the discussion thusly: “Artists should produce new designs, and fashions should be discussed more in newspapers and journals. As a basis we should study peasant and national dress. Everyone should try to clear away the mental resistance to a more varied cut and color. Then the people themselves will create new styles.”

Next, designers visit factories and villages and observe women working. Alternative fashions are produced and displayed for public comment Some favor a return to the simplicity and elegance of qipao, though most acknowledge that the high neck is uncomfortable in the summer, and that the tight skirt makes getting in and out of buses and streetcars difficult. Others prefer the practicality of trousers and jackets—one is always fashionable in them at any hour of the day or any occasion. They wear well and don’t need constant ironing. These public discussions result in a widespread awareness of the social meaning of dress in society. In the end, people turn away both from new styles and from the qipao, fearing a return to pre-revolutionary China wherein clothing was used conspicuously by the wealthy to show their elevated social status. In addition, many women celebrate trousers and jackets as symbols of their emancipation and their equality with men. The Mao suit, first an expression of an economic reality—comes to have an ideological function and in turn became the de facto uniform of the day.

For me, as an American in 2013, there’s not one answer to this debate. I am not interested in limiting myself to one garment or style. And thanks to the women’s liberation movement, I can wear pants when I feel like it, so wearing a skirt doesn’t feel oppressive to me. In the end I design a kind of utilitarian qipao. It’s looser than a traditional qipao and the skirt is above the knee so I can move freely in it. I cut it from a sturdy cotton twill fabric left over from some fabric that Damon Locks designed for the curtains in my studio. I trimmed it with leather to give it an edge. It is washable and durable. It’s appropriate for day or night. It’s crisp, clean, and uniform, and yet made of custom fabric and customized to fit to my body. It is a marriage of uniformity and individuality.

______________________

[1] Elizabeth Croll, “Politics of Dress Under Mao”. China Now (1976).

Bio Jamie Hayes’ interests lie at the intersection of fashion, art, culture, and identity. Her approach is both collaborative and customized. She believes that clothes should fit one’s body (not the other way around); that trends are largely irrelevant (people should wear what flatters and interests them rather than what someone else dictates is fashionable); that style is a form of self-expression; and that everyone in the chain of production of clothing should be paid a living wage. She has worked in the fashion industry since 1999, most notably as Design Manager of the Chicago-based custom handbag company 1154 Lill Studio, where she worked for six years. She also worked for several years in the field of immigrant and labor rights, interning at ProDESC in Mexico City and working for two years as an Organizer at Arise Chicago worker center. Her recent work merges these two paths. She has designed for SERRV, a fair trade wholesaler based in Madison, and Threads of Yunnan, a producer of fair trade embroidered textiles in Southwest China. She is currently working with Chicago Fair Trade to help pass an ordinance ensuring that City of Chicago uniform procurement is produced without the use of sweatshops. In early 2014, she will launch a line of ethically made, locally produced made-to-measure clothing for men and women called Production Mode.